The timing of sleep in relation to internal circadian rhythms, also known as the phase angle between sleep and circadian rhythms, is abnormal in many cases of N24. Here phase angle is described in terms of the relationship between sleep timing and the circadian rhythm of body temperature. In healthy individuals the body temperature starts to drop shortly before sleep onset and reaches a minimum late in the sleep period — usually about 2 hours before waking. At the same time since they are awake late relative to their temperature cycle, they are exposed to light during the phase delay portion of the phase response curve. This tends to push their circadian rhythm in the direction of a much longer than normal day. This amplifies the effect of the already prolonged intrinsic period of N24 patients.

Non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder is a circadian rhythm sleep disorder in which an individual's biological clock fails to synchronize to a 24-hour day. Instead of sleeping at roughly the same time every day, someone with N24 will typically find their sleep time gradually delaying by minutes to hours every day. They will sleep at later and later clock times until their sleep periods go all the way around the clock. (In extremely rare cases the sleep rhythm will gradually advance rather than delay.) Patients' cycles of body temperature and hormone rhythms also follow a non-24-hour rhythm.

Hours In A Week Minus Sleep Attempts to fight against this internal rhythm and sleep on a typical schedule result in severe and cumulative sleep deprivation. N24 occurs in 55-70% of completely blind people, but also occurs in an unknown number of sighted people. Their night-time sleep cycles are 4-6 hours long and this is why, at about this age, your baby might start doing these longer stints at night, waking only once or twice for a feed. You'll start to feel like a new person again after coming through the tricky and exhausting newborn phase!

We often see parents whose babies have been sleeping like champs, sometimes through the whole night, by around 12 weeks. A review of 13 studies found that regular resistance exercises performed 2-3 times a week for an average of one hour improved sleep quality. It also found that resistance exercises decreased anxiety and depression, which could be a factor in improving sleep. However, it is not recommended to do vigorous exercises such as running or interval training within one hour of bedtime.

A review of 23 studies found that healthy adults who performed high-intensity exercise too soon before bed had difficulty falling asleep and experienced poorer sleep quality. The primary means to keep the SCN clock set properly is via light-dark exposure. When the eyes are exposed to light in the early morning hours this sends a signal that advances the clock in the SCN to an earlier time, thereby providing the necessary daily entrainment. When light falls on the eyes late at night, a delay signal is sent to the SCN. A graph of the effect of light at different times of day and night is known as a phase-response curve and can be used to predict the effects of light on the biological clock.

If the SCN clock runs longer than 24 hours, it tends to become delayed relative to the day-night cycle, but morning light exposure will reset it. If the SCN clock runs shorter than 24 hours, late night light exposure will delay it a bit. By this means, the SCN clock is kept in time with the light and dark cycle of day and night.

In healthy individuals routine exposure to morning light works to keep circadian rhythms entrained. My baby is 3 months, and getting to bed isn't a problem, but staying asleep through the night is a huge issue. She's never been a good sleeper, but at this point, she is waking up around 1-2 and is fighting going back to sleep. She has a pattern of cry, fall asleep, startle, and just repeats it until I give up around 5 and end up holding her. During this time, I have attempted to feed her, because I'm at a loss for what else could be wrong, so she usually gets a few ounces twice over the course of that few hours.

I have tried to push past the 3 hour mark in the past, and not feed her just because she's fussing, but sometimes it's all I can do to keep myself sane! Like I said, falling asleep is fine, and she usually gets a solid 3 hours after we put her down. She usually goes down around 7, and we have a solid routine. Her naps during the day are erratic now, we wake consistently around 7, and her first nap is structured, but after that, she won't go down at solid times. It's a struggle to get her to sleep sometimes during the day.

Her feedings are usually good and consistent during the day. Horne's research shows that people can cut down their regular sleep to about six hours a night, plus a short nap during the day, as long as they do it gradually. In one study, he asked people who regularly slept seven to 8.5 hours a night to shorten their sleep by going to bed a certain amount of time later each night. Volunteers started by pushing back their bedtime one hour during the first week, and then pushed it back by 1.5 hours for the next three weeks.

After doing this and waking up at the same time each morning, people were able to successfully function—and get high-quality sleep—on just six to 6.5 hours of sleep each night. Another possible set of causes of N24 is related to the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. On average patients with N24 have a slightly greater sleep requirement than normal. While a healthy person may sleep 8 hours and be awake for 16 hours, if someone needs 12 hours of sleep and then is awake for a normal 16 hours, their day will last 28 hours total. The change in the sleep cycle will in turn change the timing of light exposure, perpetuating an N24 cycle.

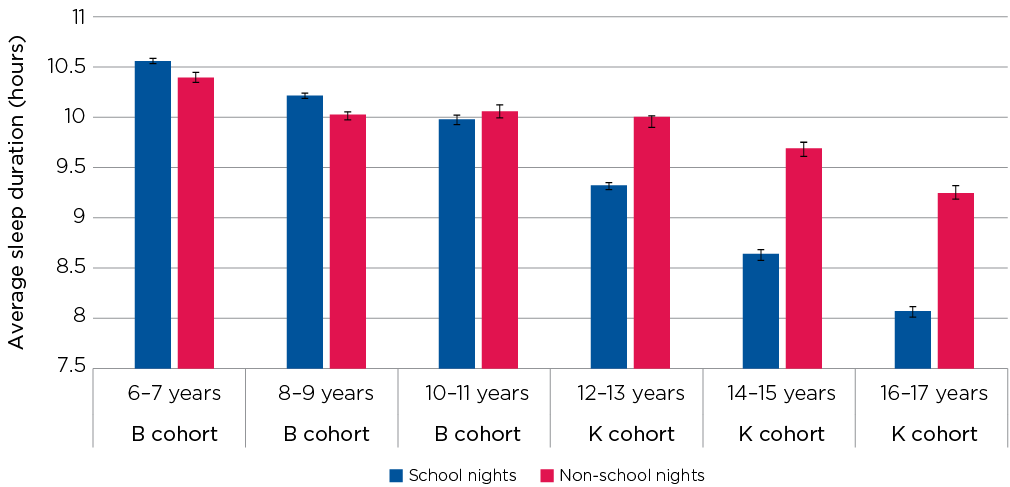

The objective of this narrative review paper is to discuss about sleep duration needed across the lifespan. Sleep duration varies widely across the lifespan and shows an inverse relationship with age. Sleep duration recommendations issued by public health authorities are important for surveillance and help to inform the population of interventions, policies, and healthy sleep behaviors. Sleep duration recommendations are well suited to provide guidance at the population-level standpoint, while advice at the individual level should be individualized to the reality of each person. A generally valid assumption is that individuals obtain the right amount of sleep if they wake up feeling well rested and perform well during the day. Beyond sleep quantity, other important sleep characteristics should be considered such as sleep quality and sleep timing (bedtime and wake-up time).

In conclusion, the important inter-individual variability in sleep needs across the life cycle implies that there is no "magic number" for the ideal duration of sleep. However, it is important to continue to promote sleep health for all. Sleep is not a waste of time and should receive the same level of attention as nutrition and exercise in the package for good health.

Studies have shown that slow-wave sleep is facilitated when brain temperature exceeds a certain threshold. It's believed that circadian rhythm and homeostatic processes regulate this threshold. An unusually low, short-term carbohydrate diet in healthy sleepers promotes an increase in the percentage of slow-wave sleep. This includes a production in the percentage of dreaming sleep , when compared to the control with a mixed diet.

It's believed that these sleep changes could very well be linked to the metabolism of the fat content of the low carbohydrate diet. In addition, the ingestion of antidepressants and certain SSRI's can increase the duration of slow-wave sleep periods; however, the effects of THC on slow-wave sleep remain controversial. Total sleep time in these instances is often unaffected due to a person's alarm clock, circadian rhythms, or early morning obligations. While sleep requirements vary slightly from person to person, most healthy adults need seven to nine hours of sleep per night to function at their best.

And despite the notion that our sleep needs decrease with age, most older people still need at least seven hours of sleep. Since older adults often have trouble sleeping this long at night, daytime naps can help fill in the gap. Irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder is characterized by the lack of a clearly defined circadian rhythm of sleep and wake. Sufferers sleep at variable times throughout the day and night with little or no apparent pattern. There are often 3 or more sleep periods of variable length during a typical 24-hour day.

ISWRD is different from N24 in that individuals with the latter have a defined rhythmic pattern to their sleep but the period of their rhythm exceeds 24-hours. ISWRD patients have little or no rhythmic pattern of any kind. ISWRD is most common among children with developmental disabilities and elderly patients with dementia. It also can result from head injury or brain tumors.

ISWRD is also known as circadian rhythm sleep disorder, irregular sleep type. This pattern may be reinforced by certain effects of sleep and wake on alertness. When individuals wake after a prolonged period of sleep, they are often in a state of reduced alertness known as sleep inertia. In people with N24 this state of sluggishness and grogginess may be very powerful and persist for many hours. The longer they are awake the more alert they become.

In addition, patients with N24 may not want to try to fall asleep at this time because they finally feel awake, alert and productive. Among the most important of the body rhythms controlled by the SCN is that of the sleep-wake cycle. This cycle is controlled by two processes known as the homeostatic process and the circadian process. During sleep the brain and body repair themselves and accumulate energy and metabolic resources for the activities of the day. During the day, while the person is awake, these resources are gradually consumed.

The gradual loss of energy during the day produces a drive to sleep in order to restore that energy. If the homeostatic process were the only one involved, a person would wake up fully energized and then gradually wind down over the course of the day, like a battery losing power. This would mean an uneven level of alertness during the day, with dangerously low alertness in the afternoon and evening. To counterbalance this, the SCN also regulates alertness by what is known as the circadian process. As the day goes on, and energy winds down, the SCN compensates for this by sending a stronger alertness signal to the brain and body. This alertness signal reaches a peak in the two hours just before bedtime.

This zone of maximum alertness is known as the "forbidden zone for sleep" since the alertness signal makes sleep nearly impossible during that zone. When the usual bedtime is reached, the SCN begins to turn down its alertness signal to allow the body to sleep. In order to prevent early awakening, before the night's sleep is done, the circadian alertness signal declines further across the night. In summary, there is no magic number or ideal amount of sleep to get each night that could apply broadly to all. The optimal amount of sleep should be individualized, as it depends on many factors.

However, it is a fair assumption to say that the optimal amount of sleep, for most people, should be within the age-appropriate sleep duration recommended ranges. Future studies should try to better inform contemporary sleep duration recommendations by examining dose–response curves with a wide range of health outcomes. Insomnia—This condition is defined as the inability to sleep or stay asleep. An individual may have a hard time falling asleep, or may sleep but then awaken in the early morning and be unable to return to sleep. Short-term insomnia can be caused by stress or traumatic events .

Insomnia often can be treated with behavioral therapies, although sometimes sleep medications are prescribed. When I sleep with my girlfriend, I get the most amazing, restorative, inconceivably best sleep of my life. Despite the only time its ever happened is in the worst conditions for ideal sleep. A hotel bed, with tropical summer heat, in a different time zone to throw off circadian rhythm, with no exercise that day, and a low carb diet. And despite 6-7 hours of sleep, it is the most well rested I've felt in my life, led me to naturally wake up without an alarm, didn't need to use melatonin to help myself fall asleep. N24 can also arise from attempts at treatment of the more common disorder, delayed sleep phase disorder .

In essence this means temporarily adopting an N24 schedule. Unfortunately, in some patients, once an N24 schedule has been established it becomes nearly impossible to break. They have exchanged one circadian rhythm disorder, DSPD, for an even more disabling one, N24. There are several reasons why the N24 pattern is hard to break out of once established. One involves the timing of sleep relative to the temperature rhythm mentioned above. The other involves what is called the plasticity of the circadian system.

That means that once an organism has been placed on a particular cycle, including a non-24-hour cycle, the circadian clock remembers that cycle and tries to continue it. The risk of N24 after chronotherapy has been known since the 1990s but many doctors continue to be unaware of the risk when recommending chronotherapy. The most well-understood cause of N24 is what occurs in blind individuals.

Persons who are completely blind will not register the light signals which are needed to fine-tune the body clock to a 24-hour day. If the SCN clock starts to drift away from 24 hours, a blind person has no intrinsic way to bring it back in sync without medical treatment. Since the inherent rhythm of the SCN is not always precisely 24 hours, a blind person's circadian timing system will slowly drift over time. They will cycle over time between periods of nighttime sleep and periods of daytime sleep. In the vast majority of cases the sleep rhythm gradually delays so the period is over 24 hours, but there are a few cases of gradual advances and a less-than-24-hour period. The length of the circadian period in blind persons with N24 is typically in the range of 23.8 to 25 hours.

First, try to figure out whether or not your baby needs to eat at night. If your baby is older than six months, you can ask your pediatrician about whether he or she is old enough to gently guide out of night feedings (some babies will be ready, some won't). See our blog about reducing night feedings or take our sleep class to create a night weaning plan. If you get the green light to rebalance her calories to daytime, then you will effectively eliminate the cause for her long waking. Once you restrict her bedtime as described above, she should start sleeping better. If it's too early to drop the feeding, then stick to your nighttime parenting behavior at night.

Go and feed your baby, but keep the lights off and keep your interactions gentle and as brief as you can. After the sleep restriction, he or she should extend her sleep further. For underlying problems with sleep associations, you may continue to have sleep-cycle wakings every 60–90 minutes , but the split night problem should resolve. Self-reported sleep duration is typically used in population health surveillance studies, because it provides several advantages .

However, the concession is that sleep duration recommendations are then largely based on self-reported data. Several studies show that sleep deprivation (i.e., regularly less than 7 hours of sleep a night) is a risk factor for obesity. A Nurses' Health Study found an association between those who slept the least and having the highest BMI and greatest weight gain. One reason may be a disruption in appetite hormones that regulate feelings of hunger versus satisfaction . A preference for foods high in fat and carbohydrate has been observed. The risk of hunger also increases simply by being awake longer, which prolongs the time from the last meal eaten to bedtime.

Insufficient sleep also can trigger the "reward" areas in your brain to crave high fat, high caloric foods. About one-third of American adults do not get enough sleep each night, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Short sleep duration in adults is defined as less than 7 hours of sleep in 24 hours. About 40% of adults report unintentionally falling asleep during the day at least once a month, and up to 70 million Americans have chronic sleep problems. Because of the public health burden of poor sleep health, achieving sufficient sleep in children and adults was included as a goal in the Healthy People 2020 goals.

In autumn, keep things as close to normal as possible. If you usually wake at 8 a.m., do it the morning of the time change, if you can (although the clock says 9 a.m.). Be consistent with eating, social, bed and exercise times, too. Raising your body's core temperature can make it harder to fall asleep, so avoid heavy workouts within four hours of bedtime. When the clocks move forward in the spring, you'll be robbed of an hour of sleep.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.